|

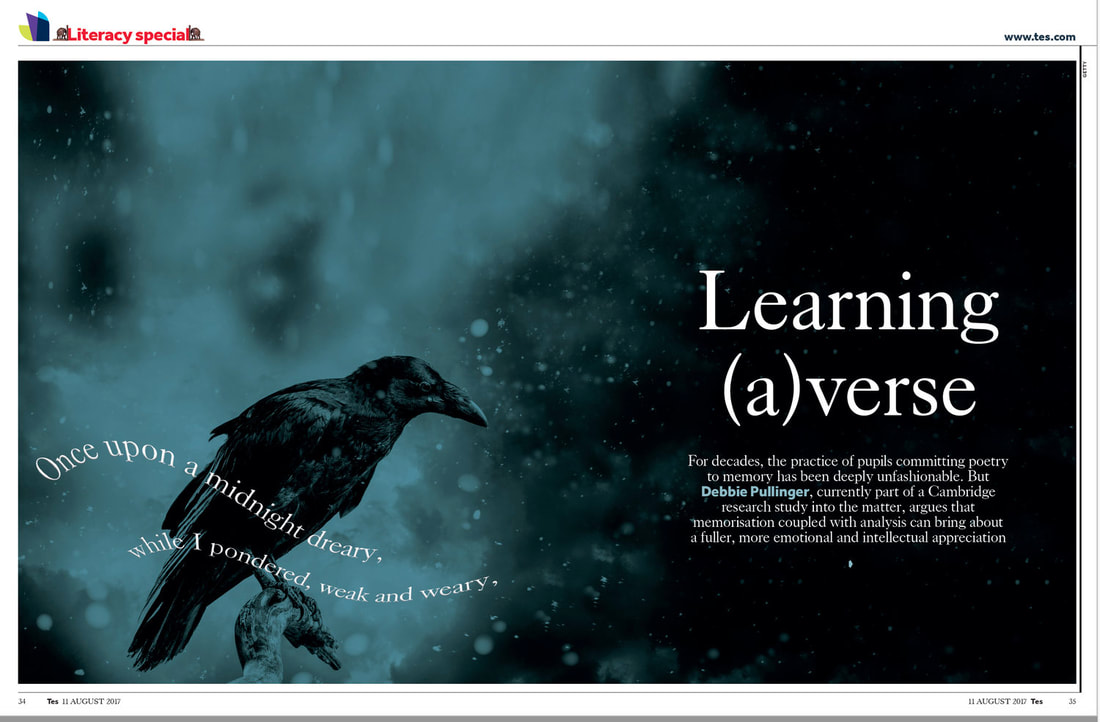

That's the title of our piece in today's TES (Times Educational Supplement). It has some rather handsome graphics, though as it happens none of the featured poems were actually picked by anyone in our survey. But I'm sure someone knows them. Full feature here.

0 Comments

On the lower slopes On the lower slopes I’ve begun to learn poetry. Actually, it’s not exactly a beginning; I did make a start earlier. I’m the generation that didn’t learn any poems at school, but I did learn a good many for speech-and-drama festivals and exams. Sadly, though I can remember which poems I learned, barely a line has stuck. So I could claim to know about three poems by heart, but none of them learned as a child. For years I assumed it was deficiency on my part, and it may be that my capacity for retention, or lack of it, played some part. But now I can also see that we were not well taught. It was all about achieving a particular type of performance, through fairly superficial advice on vocal and facial expression ; no personal, considered engagement with the poem was ever encouraged. I know I’m not alone. In our Poetry and Memory Project, there were people who described comparable experiences of losing poems learned in a perfunctory way. Equally, I should say, there were those who learned poems ‘by rote’ which did lodge, and later on unfold their meaning. (I think it's complicated!) Nevertheless, it seems to me that there are ways to learn which are more likely to create a lasting and rewarding relationship with the poem. Early on in the project, seeking personal experience of the phenomenon I was investigating, I decided to begin afresh. After some early success with Larkin’s ‘Trees’, I set my sights on some Yeats and some Herbert. They were sort of sticking, but it felt hard going and my eventually my resolve failed. Then a few weeks ago, I began afresh, afresh … And this time it’s a new world. So what’s changed? What prompted my fresh attempt was an interview with a man who had started learning poetry seriously only as an adult. At the time of our conversation he had 100 poems up his sleeve. He also said – and here’s what made me sit up – that he wasn’t actually very good at learning poetry. As he described his methods, I could see that he worked really hard at it. But his efforts had paid off. And that made me think there’s hope for anyone, even me. Thus inspired, and drawing on what I’d learned from the project, I set off once more. I can’t offer a foolproof method – or indeed any method. What I have is a few gleanings and glimmerings from many individual accounts of learning practices and processes, including, now, my own. Together, they might amount to something, but method is exactly what it isn’t. Significantly, the poetry-learning habit I’m acquiring is one that fits me and that I’ve worked out for myself. I think that’s why I found it hard to take to poetry learning apps; the strategies, and to a large extent the poems, are imposed from outside. I say that regretfully, because their hearts are in the right place and I’m loathe to criticise anything that gets poetry into people’s hands and hearts. But again, it may work for some. And whilst I’m clearing away things that didn’t work so well, I’ll just mention mnemonics. One popular technique, which is traced back to Simonides’ dinner-table disaster in the first century BC.[1] takes the form of conjuring a mental architectural space (street, house, palace) and then populating it with the objects to be recalled. And this is sometimes offered as a poetry-learning technique. Ted Hughes, for example, in his introduction to By Heart, says ‘it can systematically exploit the brain’s natural techniques for remembering’.[2] Working with the grain of the brain certainly makes good sense, and I don’t doubt that this can be an effective way to install some lines in the mind. It’s just that, for me at any rate, the mental effort required to construct and furnish my introspective setting feels cumbersome. My mental laziness aside, however, it also feels as if the superimposed locations and images divert attention away from the poem itself, obscuring the poem’s own set of integral features, and even delaying appreciation. For it seems to me that a poem is its own memory palace. The word stanza is Italian for ’room’ – a space that you can inhabit and explore. Some of the participants in our research talked about how, once they have the poem inside them, they feel as if they are on the inside of that poem. One interviewee said: “I seemed to come to know the poem from inside, as if it were a landscape that I had to navigate with my eyes closed, learning where the dips and climbs were, when to turn left or right, and what outcrops to avoid; it felt very physical.” Many poems come amply furnished with their own mnemonic fittings and features. So if we are going to exploit the brain’s natural techniques for remembering, might these be more effective when working in synergy work with the poem’s inherent memorable features? So what did work? If anything, I’d say it’s a disposition as much as a technique; a how as much as a what. It’s a learning that does not feel quite like learning so much as a 'getting to know'. I’m loathe to ennumerate tips and techniques but, with caveats in place, here are a few observations. Begin with the whole I begin with the whole poem, spend time with it, make friends with it, see what’s there, what’s lovely, what’s strange. This may sound incredibly obvious, and of course it is. But my previous learning sprees, I've been so anxious to ram the lines in that I tended to rush over this part, leaping straight to the learning. Which was completely counterproductive. No pressure Aware of the subtle self-imposed pressure to get the thing into my head, I try for a more relaxed approach. I used to feel a bit in awe of some poems, they just seemed unapproachable, which added to the self-imposed pressure. So, no rush. A certain insouciance seems to allow poems to come in at their own pace. Speaking and sharing From the off, I speak every line. Or at least mouth and breathe it (‘They flee from me that sometime did me seek’ may not be something you want to declare to the doctor’s waiting room.) And not only saying it, but saying it as if to share it with someone else. I don’t have an actual audience in mind; my listener is a pretty indeterminate figure, but effective in their role nonetheless. This vocalising or subvocalising has a number of benefits. First, I really hear the sound of the poem, which is, in substantial part, its art, and also what makes it memorable. But it’s also the sense of a sharing with someone else – which is what a poem is ultimately for – which powerfully activates the rhythm and draws out possible intonations. I can feel the way the breath runs through the line, shaped and stopped along the way by vowels and consonants. As a further spin-off, if you are learning it for a public recitation, you’re already beginning to bridge the gap many reciters report between inner recitation and public performance. Going at the poem’s pace I once read an article by a journalist who set out to learn 100 poems, and who, on the elephant-eating principle, did it by learning two lines a night. Again, I previously tried something similar, and a bit of routine to get the habit established was a good thing (until it wasn't - although that's another story!) But the two-line rule (or four or whatever) is a restriction that may cut across the sense of the poem, or both. Now, if I'm trying to learn portion-wise, I take whatever suggests itself as the next bit to be learned – which may be the next four-line stanza, or the unpacking of the next idea (usually the case in a Shakespeare sonnet, for example). And if I feel like going on further, I do. Remember mnemonics Although I find it unhelpful to impose a mnemonic scheme, such as trying to imagine the route through a poem as a walk through a house, tuning in to what one might call the poem’s ‘natural mnemonics’, and to the mind’s natural propensities, is productive. To take a very simple example: Sometime too hot the eye of heaven shines, And often is his gold complexion dimm’d; The irresistible image, however fuzzy, of a blazing sun, and perhaps even a faint sensation of heat on the skin, is worth picking up on. Now, when I get to ‘all too short a date’, I’m already glimpsing a deep blue sky and dazzling sunshine. Similarly, I found in the early stages of learning that particular poem, that I tended to stumble over the slightly awkward word order, starting the line every time with ‘Too hot’. But then, noticing the chime of sometime and shine at opposite ends of the line seemed to settle it all into place, so that along with the image I now get a foreshadowing of the line’s rhythmic shape. The end rhyme shine, furthermore, seems to pull ‘Every fair from fair sometime declines’ into earshot. Now, I realise that this might all sound just as cumbersome as the memory palace. But the things I’m describing here are subtle, almost on the edges of consciousness, and always arise naturally from the mind’s engagement with the poem. Great to get it wrong I used to be so focused on getting the thing right, that getting lines wrong– even, quite ridiculously, at first attempt – signalled clearly to me my memory’s failings, feeding the vicious circle of eroding confidence. (Of course, I completely failed to clock the parts that I did recall accurately.) In a previous life, I worked in an office. And when one of the computers went wrong we would call a man from IT. It was always a man, I'm afraid, usually with black t-shirt and ponytail. That alone made him seem like a different species, but the real test was his reaction to the problem. Shown the bit of malfunctioning that was making someone spit and growl, he would peer at the screen with genuine fascination, always with the words, ‘That’s interesting …’ I’m not suggesting for a moment that a mind or a poem can be reduced to bits of code; both are the antitheisis of mechanism. But it reminds me of an approach to problems that I often struggle to take. So, with learning a poem, the slippages can be fascinating. In the introduction to her commentary on Shakespeare’s sonnets, the poet Helen Vendler said that she found it necessary to learn them in order to arrive at the understandings she proposes. Moreover, the pieces of the whole that resisted memorisation would turn out, on closer investigation, to reveal some aspect of the design that she had missed previously.[3] Similiarly, I've found that when I attend to the bit that's causing trouble, I often discover the reason why it does not obviously and naturally follow on, either in sound or sense. Then I might see that there's a reason for the apparent 'unevenness'. And after all that – it's just that bit 'stickier'. More is more I used to think that having more than one poem on the go would lead to overload or confusion. But that thought came from a faulty, mechanistic conception of memory. In this case, less is not more; more is more and seems to work better. I’m still pondering about the reason for this. I think it may linked with keeping that more relaxed focus. If all attention is on one poem, learning is more likely to become the focus (see below). Keep looking at the poem One finding that emerged from the Poetry and Memory Project which seemed initially counter-intuitive was that people who knew a lot of poetry by heart were also the people who were most engaged with the poem on the page. They were the people with treasured anthologies, bulging notebooks, scraps of paper with verses lovingly copied and handed on. Some, too, have poems on their phones or other portable devices. So there’s no sense that the poem committed to memory supersedes the one on the page. Neither threatens the other, and the poem in memory seems to thrive in the context of a varied textual landscape. Inspired by some of my respondents, I have handwritten my poems into a book, which certainly reinforces my sense of ownership. I also have them on my phone, which is handy for a quick check on a line in a waiting-room situation. Believing is conceiving Finally, research shows that people recall better if they believe they have a good memory. I suspect this is partly because, conversely, believing one’s memory is poor tends to shift the focus away from the poem, onto the memorisation process, again creating counter-productive anxiety that tends to short-circuit the process of recall. As we all know from trying to recall a name, memory just seems to work better if you just leave it to get on with the job undisturbed. Sharing with real people I haven’t yet got to the stage where I can supply an apt line for any occasion (as a few of my enviable interviewees seemed able to do), but I am finding that lines are coming to mind more readily. I’ve also recited or shared lines in the context of talking about the project and about learning poetry for performance. I rarely go beyond about four lines, but still it bolsters my sense of connection with the poem. Keep looking at the poem It may now be apparent that much of the above has been about keeping attention away from the process of recall and on the poem, about getting myself out of the way. As with many things in life, learning by heart may be best achieved as a by product. Notes [1] Cicero records a story about banquet in Thessaly, attended by the poet Simonides. After his performance, Simonides went outside briefly, during which time the roof of the hall collapsed. All the guests were killed and their bodies crushed beyond recognition. Simonides found he was able to identify the bodies by recalling his mental image of the table, and the place of each guest. From this, as Cicero said, he inferred that persons desiring to train their memory could ‘select places and form mental images of the things they wish to remember and store those images in the places, so that the order of the places will preserve the order of the things’ (Cicero, De Oratore, II, lxxxvi – translation: Sutton & Rackham, 1942). [2] Hughes, T. (1997). By Heart: 101 Poems to Remember. London, Faber and Faber. [3] Vendler, H. (1997). The Art of Shakespeare's Sonnets. Cambridge, Mass. and London, Harvard University Press.  It's been a long time since the last blog post. This is because I've been up to my ears in survey data, and also travelling round the country interviewing some of our survey participants. If the survey data is interesting, the interviews have been utterly compelling. I have listened to wonderful stories of how poetry comes into a life and how a poem may travel through a life, carried within the heart. As with the survey data, the most striking thing is the sheer variety of experience. People relate to poems in such different ways. We are still working with our data, and trying to tease out what it all means. In the meanwhile, public interest in memorised poetry continues. At the Hay Festival recently, Salman Rushdie described it as a “lost art” that “enriches your relationship with language”. Picking up on the remark, the Guardian reporter, wrote, somewhat unfortunately, about rote learning. But she did ask us if we agreed. Read more…  One nice thing about this project is that, as research goes, its point and purpose are easy to convey to colleagues or friends or casual enquirers. The reactions are also interesting in themselves. Many people initially assume that we’re doing some kind of testing on children. It’s a reasonable assumption: we are, after all, based in the Faculty of Education. And ultimately, if memorisation and recitation foster the kind of engagement with a poem that we want young people to have, then this research will surely have implications for policy and practice. But although we’re planning to do some work with some schools later on, this is by no means the main focus. Whilst there is a place for educational research in schools, there is also case for research that doesn’t begin with the child in school but begins with human being. As Professor Teresa Cremin said recently, “rather than beginning with teachers and children, we begin with people – people reading, people writing and so on, and then build up the pedagogy from there.” * This seems to us especially important in the case of poetry. For poetry’s time is not necessarily the time of the English period or the GCSE syllabus. A poem’s work in us may be slow and unpredictable. So whatever research in school were to tell us, it’s possible that it would not be the whole story. As the poet Charles Causley said: “As the poet Charles Causley observed: ‘if, say, 80 per cent of a poem comes across, let us be satisfied. The remainder, with luck, will unfold during the rest of our lives.’ (Causley 1966, p. 91). As it turns out, poetry has its own time in terms of our survey, too. We’ve had many wonderful responses already – and still they’re coming in. So, although the original plan was to keep the survey open until the end of October, we’re going keep it open a little while longer, allowing time for things to unfold a little further. Debbie Pullinger * Keynote speech at UKLA 50th International Conference, University of Sussex, 2014  In the news today is Dame Judi Dench's revelation that she learns a poem every day to keep her mind active. This tidbit is as tantalising as it is exciting. It would be fascinating to find out how many years she has been doing this, whether she could still remember the poems she has learned, are there any poems that seem to pop up in the memory … and so on. (If only she could be persuaded to participate in our survey!) Equally of interest to me is what she says about where her love of poetry came from. Asked in an interview at the Stratford-Upon-Avon Poetry Festival whether there was poetry in her family, she replied. “Absolutely – my father would come upstairs in a morning while I was asleep and wake me up with verse: “Awake, for morning in the bowl of night has cast the stone that puts the stars to flight”, he would shout in my bedroom. Daddy knew the whole of Tennyson’s Morte D’Arthur by heart, he was a lovely man.” In our previous research project, a much smaller study of local poetry teachers, we found that the teachers who knew some poetry by heart had all had a parent who recited poetry to them as children – and it was nearly always a father. Our sample was by no means large enough to make any claims about this, but evidence from this other sources certainly supports the idea that poetry is transmitted in vivo. And the idea that it might tend to come down through fathers is a most intriguing one. Did you ‘inherit’ a love of poetry? Do come and tell us about it! Debbie Pullinger Yesterday, I met one of my neighbours on my street walking his dog. “Didn’t I see you on the telly?” he said. “Yes,” I admitted, a bit sheepishly, “that would have been when we launched our survey” – and I explained briefly what it's all about. “Oh, that’s really cool!” he said. And he meant it.

That was a fairly typical reaction. There’s something about this project that seems to have immediate connection for many people. But I'm still being constantly surprised. When I met the dog-walking neighbour, I was in fact on my way out to a College dinner where I’d arranged to meet a friend. As we sat down at the table, she leaned across and whispered excitedly, “You know, you are surrounded by people who know poetry!" You see that tall man on the next table. He can recite some Hamlet. And the girl next to him – she knows Shakespeare’s Sonnet 116. And the man next to her … It turned out that last Thursday she’d heard the piece about National Poetry Day on Radio Four's Today programme (though not really aware that it was our project) and made it her mission that day to find out what poems people in the college knew. During the course of the evening, I met several of them who gamely recited one or two lines. I found this an intriguing idea: the notion we were at that moment surrounded by little pieces of poetry, living inside people. Like underground springs, they’re invisible, but bubbling beneath the surface and potentially life-giving. You might imagine my enterprising friend was an English scholar, but she’s actually an architect. But then, as Goethe said, architecture is frozen music.  Seeing all the responses start to come in last week was quite an emotional moment for me. Partly it was sheer relief: the realisation that it’s actually worked; we’re going to have some data worth the analysis. Partly it was seeing the thought, care and enthusiasm that so many people had put in to their responses. I’ve started to put some up (anonymised) snippets, hoping that, like the audio they might act as a spur to reflection. And today was another milestone – the arrival of our first ‘print-and-post survey’. If you know anyone who doesn’t have access to the Internet who’d be interested in participating, and can print one off for them, we'd be most grateful! Debbie Pullinger  The Cambridge News gets the measure of it. The Cambridge News gets the measure of it. National Poetry Day may be over, but it’s still Poetry and Memory Month! Our survey, which runs throughout October, has already got off to a great start. When we launched on Thursday, the project was featured on Radio 4’s Today programme, ITV Anglia News, and Radio Scotland’s Culture Studio. And our own Cambridge News rose to the occasion in poetic mode. (Click the image to view.) That first day also brought – to our huge relief – a surge of survey responses. We’ve also had lots of messages from people expressing interest in and support for the project, along with various questions. So here on our first ‘Live Survey Blog’, I thought I’d deal with a few FAQs. (All genuine questions and comments.) I was born in the UK, but I don’t live there now. And I’d love to take part – why can’t I? One of the aims of the survey is to try and build up a picture of poetry that people know today in the UK, so we didn’t want to complicate that particular issue by extending the survey beyond its borders. However, it has other aims that relate to our wider investigation. We’re also interested in what people who know a poem by heart have to say about that poem, how they feel about memorised poetry, and where and why the poems have been learned. So we’ve now set up a separate survey which is open to anyone from the UK but currently living abroad. You can do that survey here. So, do you think our experience of a poem is really different when it’s in our memory, and what are the effects? We don’t know yet. There’s virtually no research on this; that’s why we’re doing this. (We do have ideas, of course, but we don’t want to pre-empt the actual findings.) This is fascinating! When and where can I find out the results? We hope to post some of our ‘headline’ findings here on the website not too long after the survey has closed. These will be some of the results of the initial quantitative analysis – the most frequently learned poems and poets, the age at which poetry tends to be learned, and so on. However, if you’ve done our survey, you’ll know that we also ask a couple of more open-ended questions. The analysis of this qualitative data – which, in turn, we will be looking at in relation both to the other elements of the survey and to work within the wider investigation – is going to take a great deal longer. But again, we will put news of when and where our findings are published on this website. That’s a long time to wait. It is. But then good research, as opposed to a quick poll, takes time. In the meantime, we've got a daily snapshot quote on this blog and survey page. I registered for a reminder but I didn’t get one. We sent them out on Thursday but there were a very small number of email addresses that bounced back. Apologies if that was one of yours. I know a Pullinger. Are you related? Yes. No. Perhaps. But only sort of.

And just last year, Radio 4’s Poetry Please analysed all requests to the programme to reveal that, most of all, listeners would like to be stopping by woods on a snowy evening with Robert Frost. Our aim, however, is rather different. We want to discover what poems people know by heart – what poetry resides in our collective memory. To the best of our knowledge, this is first time a survey of this kind and scope has been attempted.

Had we been doing this research a hundred or even fifty years ago, the results would doubtless have been more predictable. Up until 1944 the memorisation and recitation of poetry was prescribed on the school curriculum, and children memorised certain ‘staple poems’, which, as Catherine Robson records in her fascinating study, Heartbeats,* had lasting effects on those who learned them. But in the second half of the century, poetry learning became deeply unfashionable within education – the baby thrown out with the rote-learning bathwater. And yet, many people do still know a poem or two, for all sorts of reasons. So that’s what we’d like to know: what are the poems that live in people’s memories, at this moment, in October 2014? For some, it might well be a ‘favourite poem’, but that doesn't necessarily have to be the case for everyone. What does the survey involve?We’re asking anyone who has a poem in their head to come and tell us about it. So the central questions are, what poem do you know? And when and why did you learn it? It can be any poem, and any type of poem – we just ask that it isn’t a song lyric or a nursery rhyme. Secondly, we’re asking a couple of fairly open-ended questions about what this poem means for you. The important thing here is that we’re emphatically not looking for GCSE English answers, or an analysis of what the poem is ‘supposed to be about’. Rather, we want to know what significance this particular poem holds for you. This might be to something do with the meaning, but it could also be to do with the sound. It may be that there’s one line which is particularly special. It may be that how you understand or feel about the poem has changed over the years. It may be that you associate the poem with a particular occasion or period of your life. Or, it could be that the poem you know actually has very little meaning or significance for you at all – and we want to know about that, too. And you can write as much (or as little) as you like for these questions – it's up to you. Finally, we also ask for a few personal details: gender, nationality and so on. What are we hoping to find out?Straight off, we expect to be able to announce what poem or poems beat most strongly at the heart of the nation. But aside from a headline top ten and other vital statistics, there’s a great deal more that we’ll be able to do with this data. We’ll be able to investigate, for example, the reasons why people now learn poetry, and the perceived value of doing so. We’re particularly interested in questions about the ‘use’ of learned poems – how they might act as an emotional resource, contribute to a sense of identity, assist in the development of an ear for language, engender a sense of community, play a role in memories of a personal or communal past. What, in fact, is distinctive about this form of relationship with a poem? What does knowing a poem mean for someone, and indeed what different things does it mean for different people? Poetry and Memory needs YOU!We’ve worked hard on developing this survey, and we’re really looking forward to seeing the responses and sharing some of the results. But, of course, its success as a piece of research hangs on getting a good response – which means we need lots of people to take part. So we really do need your help. You can do this in two ways. TAKE PART IN THE SURVEY – if you have a poem in your head, please come and tell us about it. SPREAD THE WORD – even if you don’t know a poem yourself, do pass the word on to family, friends, neighbours and colleagues. We should also mention that it will be possible for print out a copy of the survey to give to anyone unable to access it online. They can then post it back to us using the Freepost address. You can get spreading any way you fancy. Phone a friend. Find us on Facebook (The Poetry and Memory Project). Tweet on Twitter (@poetryandmemory #poetryandmemorysurvey). Print a poster and display it on your favourite notice board. And if you have any other ideas … let’s be having them! Whatever you can do, we’ll be enormously grateful. Debbie Pullinger * Robson, Catherine (2012) Heartbeats: Everyday Life and the Memorized Poem. Princeton and Oxford, Princeton University Press.  The Poetry By Heart semi-finals at the National Portrait Gallery on Friday was a great excuse to get away from the desk and head down to London. For anyone who hasn’t caught up with this splendid initiative, Poetry By Heart is a national competition, now in its second year, in which 14–18 year olds are invited to learn and recite three poems, choosing from a wide, rich selection in the Poetry By Heart anthology. Schools hold classroom then whole-school contests, with winners progressing to county then regional heats. As a member of the audience, I was handed a card which asked us to write down how we would describe to a friend what we had seen and heard.[1] It was question that I felt really required the resources of poetry to be supply anything like an adequate answer. I’ve been trying since last Friday to take the persistent image in my mind’s eye – iridescent bubbles, carrying the breath of the poet and the performer momentarily into the air – and make it into something half-presentable, but it hasn’t quite come together. (Yet.) But what did we come to see and hear? What did we see and hear? A competition? Possibly. But competition was not the prevailing mood. The event had more of an air of celebration, festival, or party. With all the performers in each semi-final seated together on the stage, each individual performance seemed held by the little group, supported from behind as well as from before. A coming together. A culmination? Months of hard work come to fruition? It almost certainly was for everyone involved. But equally, it felt like opening, rather than a closing: a sort of T.S. Eliot moment, where ‘to make an end is to make a beginning’. For me as an audience member, it felt like a journey of shared discovery as we and the performers discovered new meanings in each poem, and fresh responses to old favourites in ourselves. In this, as poetry readings go, it was exemplary. A standard being set? Unavoidably, perhaps. But equally, in our current educational regime of targets and tick boxes, it seemed that here was a much more open-minded and generous approach. The diversity and the individuality of the performances was astonishing. But this was never a self-conscious individuality for its own sake; rather, an authentic interpretation forged out of each honest, unique encounter between reader and poet. Over just a couple of rounds, a few poems came up twice, with no fewer than three outings for Browning’s Porphyria’s lover. The same poem and yet a completely different poem: a different encounter with the poem and poet. This form of comparison in itself highlighted some interesting questions about the interpretative choices that open up as soon as a poem is spoken aloud. M’colleague and I certainly didn’t always agree in our own little private voting huddle. “She really brought out the rhythms of the poem.” “True, but wasn’t always sure about some of the enjambments, like at the end of that line …” “Oh but I liked the way she did that!” Different encounters between listener and performance. A performance? That’s a tricky one. Interestingly, the poet Jacob Sam La Rose, our very cheery compère, mostly referred to the competitors as ‘readers’, or, on the odd occasion, as ‘poets’. (A trip of the tongue that the poet himself acknowledged was rather telling.) His dilemma, I think, was real. Somehow, ‘reader’ didn’t seem quite right for what we were seeing and hearing; nor, perhaps, would ‘performer’. The word performer stems of course from performance, which has multiplying sets of meanings and a complex set of connotations – none of which seem quite to encompass the act of creativity taking place in the moment as the poem is spoken aloud. Similarly, reader and reading, which might indicate either reception (as in to decode and voice the words on a page) or a more active act of interpretation. The way we use all these terms raises quite profound questions about the voice and role of both the writer or composer and the reader of the poem. Exactly who is speaking? This is not drama where an actor seeks to take on the voice of the character.[2] In the course of a fairly complex argument about poetic interpretation, Christopher Collins argues that in writing a poem, a poet effectively splits himself to become both the speaker and the listener (or the addresser and the addressee). The reader, on the other side of the page, as it were, is invited into an act of poetic play or performance as they respond to the text and use their own voice to effectively impersonate the speaker.[3] By taking the part of both speaker and listener, a reader thus assumes a ‘multi-voiced central consciousness’ and thereby a centrality within their perceived world – a ‘degree-zero here-and nowness’. So, in other words, when we read a poem, the voice within the poem and the voice from within ourselves blend to become that which we speak. All of which is to say that it seems that at the moment we do not have a language for what we are hearing and seeing, perhaps because the words we used in the past have, as it were, ‘moved on’. Or, I wonder, are there words that we have forgotten we knew? I was fascinated to read the other day that in the days when memorisation was a celebrated art, the lexicon of terms was much bigger than it is now. I wonder if there could be any similar lost words associated with recitation?[4] In reclaiming poetry recital (recite, interestingly, is another word with those positive and negative resonances) we are struggling to find words for things that we have forgotten, or forgotten how to describe. As in writing poetry, we find ourselves at the very edges of language. At the end of each round, Sir Andrew Motion came to the front of the stage to announce the winner. Judges and adjudicators traditionally begin by emphasising what a terribly difficult task they faced and their extreme reluctance to single out a victor. But we all felt that this time it was for real. Debbie Pullinger ________________________________________________________________________ [1] If you were there, and didn't fill in your card, do feel free to leave a comment here – we’ll make sure they get it! [2] One could argue that this is the case in a dramatic monologue, as for example in the Browning poem. But even there, it can also be argued that this is still a poem, in which the words are still subject to all the formal structures of poetry, that the poet is using this device to express something that could not otherwise convey using a voice closer to ‘real life’ or their own. And so it asks to be read with that sense of doubleness. [3] Collins, C. (1991). The Poetics of the Mind’s Eye: Literature and the Psychology of Imagination. (p.58) [4] Edward Casey notes the dwindling of the memory lexicon, that used to include such words as: memorous, meaning ‘memorable’, memorious, meaning – ‘having a good memory’, and (my favourite) memorist – ‘one who prompts the return of memories’. Casey, E. S. (2000). Remembering: A Phenomenological Study. (p.5.) |

AuthorArchives

August 2017

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed